In the News

How UCD research of rare genetic mutation could unlock clues to Alzheimer’s, cancer

Source: The Sacramento Bee

Medical researchers know the enemy that 12-year-old Jordan Lang and at least 66 other children are confronting. It’s a gene mutation that also has been linked to autism, Alzheimer’s disease and even cancer.

What researchers lack is a treatment or cure and — until now — the funding for the work they must do to find one, said UC Davis researchers Kyle Fink and Jan Nolta. Fink points out that other perplexing, rare genetic disorders now have treatments:

In Columbus, Ohio, for instance, Dr. Brian Kaspar worked with a French team to develop a one-time gene therapy treatment – delivering a missing protein via a virus — that gave muscle control and mobility to infants with a genetic disorder known as spinal muscular atrophy type 1. Typically, the illness gradually paralyzes the children and ends in early death.

There is also Dr. Donald Kohn who led a team at University of California, Los Angeles, in developing a stem-cell gene therapy that has safely restored the immune systems of a number of infants born with so-called bubble baby disease. Infants who have the rare illness don’t have a crucial enzyme that helps them fight off infections, and they typically die before their first birthday.

“This is really precision medicine at its finest,” said Nolta, director of the UC Davis Institute for Regenerative Cures in Sacramento. “Precision medicine is all about finding the gene that is responsible and then trying to find drugs or treatments or gene modifications … that could actually make an impact on the health care of that child.”

Nolta and Fink learned in June, when California Gov. Jerry Brown signed the 2018-19 state budget, that they would get the funding for the collaborative research needed to find a cure for Jordan’s syndrome, a genetic disorder that can result in symptoms such as autism, intellectual disabilities, behavioral challenges and seizures.

State leaders set aside $12 million from theCalifornia Initiative to Advance Precision Medicine, a fund Brown launched in 2015, to help establish the infrastructure and identify resources to support this work. Jordan’s father, Sacramento-based lobbyist Joe Lang, worked with State Sen. Richard Pan and UC Davis officials to get the funding.

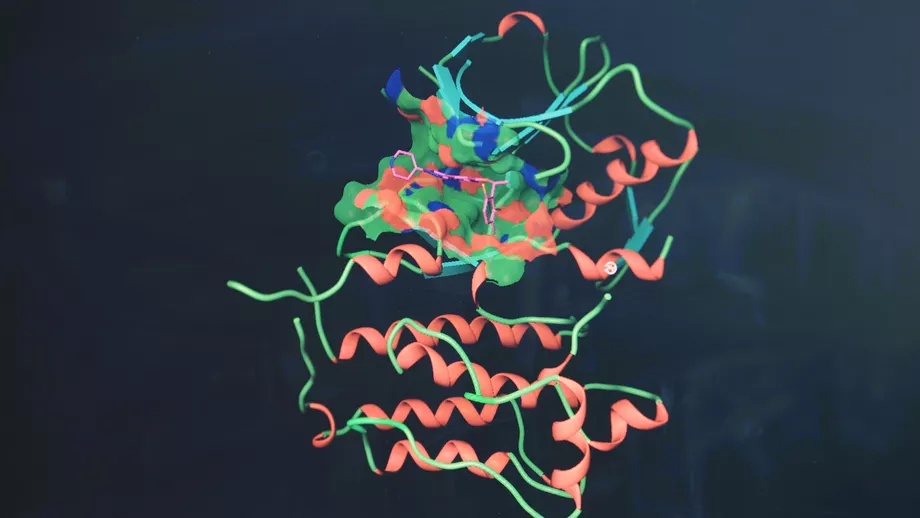

The UC Davis will administer the state funds and lead a team of researchers at eight institutions around the world trying to better understand the disease and come up with cures in the next three to four years. Fink, an assistant professor of neurology who works on Nolta’s team, has spent years studying genetically linked neurological diseases and how to develop therapies for them.

He’s looking at all different tools that can change how bad genes are behaving. What traits can be turned off? What traits can be kickstarted? The goal is to help Jordan and other children like her develop normally.

The genetic disorder was given the name Jordan’s syndrome because Jordan was the first child diagnosed with it in the United States. While the genetic mutation has likely been there forever, Fink said, it wasn’t until Jordan’s genome was mapped in 2014 that U.S. researchers put the mutation into medical registries that document such conditions.

“They are averaging a new patient every week who’s diagnosed with this now,” Fink said. “I think that’s going to grow as coverage of this and knowledge of this increases.”

Since 2017, Jordan’s Guardian Angels, a foundation started by Jordan’s parents, already had funded $1.5 million in research by an international team of clinicians and scientists, but the group knew they would need millions more dollars to find a treatment and get it through a clinical trial.

“Right now one team getting a single grant has about an 8 percent chance of being funded by the National Institutes of Health,” Nolta said. “The state funding supports nine teams at multiple institutions who are studying diverse aspects of the disorder, which is like each team getting an NIH grant for two to three years to work full time on Jordan’s syndrome. The impact of the appropriation is tremendous.”

Nolta and Fink said it’s unheard of to get that kind of financial support from NIH for an orphan disease such as Jordan’s syndrome. Yet, Fink said, by understanding Jordan’s disorder, researchers can start to learn more about cell growth, cell degeneration, cancers, plaques, proteins and healthy aging.

“Everything we could learn with Jordan’s Guardian Angels,” Fink said, “I think we can immediately turn around and apply the knowledge we’ve gained to the kids who are suffering from Juvenile Huntington’s disease. I can turn around and apply that technology to kids who have Angelman syndrome. … You start to build up these knowledge bases and these platforms, and these tools can cross-pollinate for other things.”